J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator

Hammond, Wayne G. and Christina Scull. J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator. Houghton Mifflin hardcover, 1995, $40, 208 pages, 200 illustrations. ISBN-13: 978-0618083619

(This review originally appeared in Mythprint #175 in July 1996.)

Reviewed by David Bratman

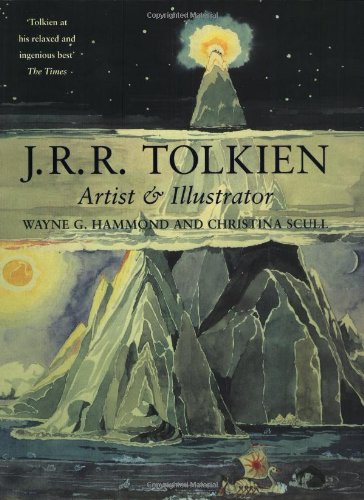

Everyone who’s read The Father Christmas Letters or Mr. Bliss or the hardcover edition of The Hobbit, or who’s seen Pictures by J.R.R. Tolkien, knows that Tolkien was a magnificent illustrator of his own works. Even leaving aside the condescension that may be read into the word “illustrator,” we may go so far as to say that Tolkien was a great artist of landscapes, especially imaginary ones. The magnificent view of Taniquetil reproduced on the jacket of this book proves that all by itself.

This magnificent volume is a full, detailed, and definitive study of Tolkien’s artwork in all its manifestations, with 196 excellently reproduced copies of his art. (The other four illustrations are of artwork by others which inspired Tolkien’s illustrations in The Hobbit.) Of these, 105 are in color, and 67 of the remaining 91 were drawn in black and white anyway. So this is a glorious feast of Tolkien’s artwork. A few of the fainter features described in the text may be hard to see (the face on the sun in number 26, for instance), but look hard, because they are there.

Besides a visual feast, the book is an eye-opener. The lengthy chapter on The Hobbit recounts in detail how its various well-known illustrations were teased out and redrafted, bit by bit. All of the published illustrations are included (mostly reproduced directly from the original art), as well as many earlier drafts. This includes the dust jacket, and after reading that you may want to turn several pages, past various Lord of the Rings illustrations, to the remarkable and arresting unused dust jacket designs Tolkien drafted for this work.

Many of the other LotR illustrations have been seen before (but not all of the various designs for Orthanc, a structure whose evolution the text discusses in detail), but there is much in this book that will be totally new to almost all Tolkienians. Just about all the first half of the book, for instance. Besides a generous enough selection from the previously published Father Christmas Letters and Mr. Bliss to illustrate the text’s points, the book includes five illustrations from the unpublished Roverandom, including a fine Thomas Hart Bentonesque farm landscape, and the truly breathtaking undersea “Gardens of the Merking’s Palace.”

The first chapter covers Tolkien’s (mostly early) British landscapes and artwork depicting buildings, and his few portraits. His meticulously drafted impressions of the world around him have not been seen before. Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull climbed everything from hills to abandoned fire escapes to identify exactly where Tolkien set up his sketchboard or easel and what he was looking at, and this meticulous research serves the text well.

Chapter two, “Visions, Myths, and Legends,” is key to understanding Tolkien’s imagination. His unexpected and intriguing concrete depictions of abstract concepts, from “Before” to “Eeriness,” have never before been seen or even hinted at, but they lead directly into his brightly colored depictions of mythic landscapes, also new to print, and from there to the Silmarillion illustrations of the late 1920s. These last have been seen before, but the context and the informative text commentary make you see them in a new way.

From there, the reader proceeds into the chapters on the children’s illustrations, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, a final chapter on patterns and heraldic devices, and an appendix on calligraphy.

How does this book compare with Pictures by J.R.R. Tolkien? In terms of text, there is no comparison whatever. The brief captions in Pictures are mostly devoted to describing provenance of publication. Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull’s text here would be a full book’s worth even without the artwork itself. In it, they discuss Tolkien’s artistic principles and interests, the literary background of the illustrations to his books, the physical context of the drawings from life and how they influenced the mythology (the home named Gipsy Green evidently inspired Gilfanon’s house at Tavrobel in The Book of Lost Tales, for instance), and the technical problems attendant on the art intended for publication.

About three-quarters of Tolkien’s artwork in Pictures is reproduced in this book, usually smaller in size but often more clearly and usually in better color. The overlap, and the exclusions, are designed to enable this book to cover Tolkien’s art thoroughly and completely without rendering Pictures superfluous. For instance, since Pictures contains several versions of the Tree of Amalion, this book reproduces just one, devoting its multiple-version coverage to other matters. Since The Father Christmas Letters is easily available, this book does not duplicate Pictures’ selection from that. Tolkien’s pattern designs from late in his life are extensive, so this book chooses an entirely different selection than Pictures. A few early drafts of particular scenes from Pictures are not included here, but this book makes up for that by including other previously unpublished drafts of the same scenes. I was only sorry not to see all three facsimile pages of “The Book of Mazarbul” here — only the third is included — but this book makes up for that by including a draft version of page one.

As with “The History of Middle-earth” series, so with Artist & Illustrator. Few authors are fortunate enough to have their works served so well.